jazz and the dream of equality

It is entirely fitting and proper for Art and specifically Jazz to be part of this celebration of the life and work of

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. His dream so richly and poetically described and foretold a better and more

harmonious place. We have only now, 50 years later, begun to see hints of Dr. King’s vision, but we know

in our souls it will happen. We go forward today, as he exhorted us to then--because we believe in the

picture he painted, the song he sang, the poetry he spoke.

Art is a moment frozen in time. It is given life, meaning and a point of view by the Artist in a medium of his choice, in such a way as to touch deeply our emotions.

Dr. King’s “I have a dream” speech is itself a magnificent work of Art. During that era of racial

unrest in a country on the brink of madness, this great artist assessed his time, knew where his

country had been and knew what it could become. His medium was the word and the human voice.

He touched people of every color and showed them that a better way to live existed within their own hearts.

We cannot dream something unless it has been experienced (no matter how rudimentary or base the

form), i.e., a winged horse because we understand “wings” and we understand “horse.” So where was

that color-neutral--if not colorblind—space in America where Dr. King could extrapolate the foundation

of his dream? That place where communication and mutual respect thrived with so little friction?

That place, of course, was Jazz.

It is ironic and yet so very American that its most disenfranchised citizens created the first two truly all-

American music styles: Jazz and the Blues. And Jazz was born in New Orleans--that most foreign of all US cities. “Our” music didn’t arrive on the decks of the Mayflower but rather in the belly of slave ships.

Jazz met with closed doors in polite society. It is nearly inconceivable to those who have never seen a black-and-white movie that there was a time before radio and records when music was hawked on comers and sold as sheet music,

primarily to be taken home and sung. A “hot” song in Chicago

might never get to Manhattan. And, yet, Jazz traveled from New Orleans to New York City as fast as any of today’s downloads.

This energetic brothel music with its tantalizing beat landed on the Lower East Side as well as Harlem—and was embraced by another group of disenfranchised artists. The 1920s were three generations removed from slavery, but it was still not enough. We were a nation so divided that there was absolute denial of the divide. The music might have been segregated, but artists like Irving Berlin and George Gershwin were inspired by artists like Louis Armstrong and Jellyroll Morton. These musicians who embraced the syncopated rhythms added the melancholy and romantic melodies that were woven into their DNA. Here was communication based not on Creole or Yiddish or southern slang or Patu, but rather on sharps and flats and eighth notes.

By the 1930’s and the Great Depression, the racial divide could no longer be denied. In times of stress, the weakest suffer more. Lynchings—one of the most chilling words in any language—uncovered the sad fact that inhumanity knows no color. A particularly shameful photo appeared in the 1930s of a lynching in daylight where white men women and children stood and watched as if it were entertainment. Their faces showed no horror but ranged from boredom to glee. This was not in the South but in Indiana. For the most part ,America was silent.

And then four people--through Jazz--made statements so profound that they turned the tide. The seeds of change in America were sown in large part with two songs that brought together two black singers and two New York Jewish songwriters.

Suppertime and Strange Fruit

The two singers: Miss Ethel Waters (the first Black woman to receive equal billing with her white co-stars on Broadway) and Billie Holiday, the first Black woman to sing in an integrated Big Band. Both of these extraordinary artists were forced to appear as “white” as possible to be “accepted.” Both suffered backlash, and to our everlasting shame, only experienced “equality” with their Jazz compatriots.

The two Eastern European Jewish immigrants: Abel Meeropol, a teacher in the Bronx, felt he had to become “Lewis Allan” in order to get his song/poem published and recorded. Israel Isidore Baline’s name doesn’t appear on one

of his songs, but “Irving Berlin” does. Ironically, Berlin wrote what many consider to be the quintessential American anthem, but God Bless America wasn’t in the running for official recognition because members of Congress had no problem condemning its author as a Jew.

The power of Art surging through these four people in these two songs made America really look at itself and begin to be ashamed of its color lines. The collaboration it took to do this was not black or white or Christian or Jewish: it was Jazz.

Jazz integrated long before sports or any other forms of entertainment did so, long before defiance arose about

where to sit on the bus or at a lunch counter. Jazz--no protest, no pickets or bombings--just got on with it.

In 1936 at Chicago’s Congress Hotel in front of segregated café society, 28-year-old Benny Goodman changed everything when he simply invited Lionel Hampton and Teddy Wilson to sit in with his band. The invitation was not extended because these men were Black. It was not extended because it was the right thing to do. It was extended because of their talent. Period. And that was what Dr. King sang of in his dream. The and the only riot was enthusiastic applause.

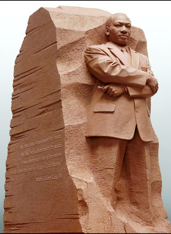

The 1950’s sit-ins and 1960’s protest marches were still decades away, yet Dr. King’s dream of a time of true equality was not sewn out of whole cloth. The stunning new monument on the National Mall pays tribute to a great man. But we should also remember and honor the foregoing three magnificent moments that in their own ways enabled his dream.

Jazz

an opinion: